The Elusive Banknotes of New Sudan

Peter Symes

As Sudan comes to terms with the overwhelming vote in January by the people of southern Sudan to break away and become an independent state, the question of currency in the new nation will intrigue collectors. However, southern Sudan already has a history of currency distinct from the national currency. There was an unofficial issue of New Sudan notes well ahead of any formal independence for the south. These already pose a challenge for collectors.

A little background is necessary. Sudan, one of Africa’s largest countries, is split into the north and the south along racial and religious grounds. The north is populated predominantly by Arabs who are Muslims, while the south is mainly populated by Black Africans who are Christians or animists. Since independence in 1956, Sudan’s government has been dominated by representatives from the north, while those in the south have played a lesser part in government.

The imbalance in power sharing has led to friction over many years, leading to civil wars and disturbances which have wracked Sudan for most of its existence – costing millions of lives. In 1983 guerrilla groups in the south formed the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA), led by John Garang. The movement later generated a political arm called the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM), and the two organizations are usually abbreviated as SPLM/A . The SPLA fought against the government of Sudan along side several other groups for many years. In 1989 the SPLM/A joined the National Democratic Alliance (NDA), which sued for peace and recognition of the south.

Peace did not come quickly and after many years of war and struggle, and with international assistance, in 2005 the NDA signed the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) with the government of Sudan. The CPA is a complex and challenging agreement, which allows for two systems of administration within Sudan. For instance, the Central Bank of Sudan operates as two entities, the Central Bank of Sudan in the north and the Bank of Southern Sudan (BOSS) in the south. In the north, the bank operates under Islamic banking regulations, while in the south the Bank of Southern Sudan operates under traditional banking principles. The CPA was tested in January this year when southern Sudan held the referendum to determine whether to remain a part of Sudan or break away as a separate state.

The southern Sudanese saw the introduction of a new currency with an Arab name as part of the northern government’s program to impose Arab culture on the south. Consequently, in many parts of the south there was resistance to the introduction of the new currency. The dissatisfaction with the new currency festered for many years and in various parts of southern Sudan a range of currencies circulated in an effort to reject the new dinar. In Yambio and the surrounding areas the Ugandan shilling and the old Sudanese pound were used; in the south and the east of the southern region the Kenyan shilling and the Ethiopian birr were preferred; around Rumbek, where many of the aid communities were headquartered, the US dollar, the Kenyan shilling and the old Sudanese pound circulated; while in Bahr el Ghazal and other areas bordering the north, the dinar was the dominant currency in circulation.[1]

The range of circulating currencies and the lack of economic stability in southern Sudan led the SPLM/A to consider the introduction of a commercial bank, to stimulate economic activity, and to introduce their own currency. The possibility of introducing a bank to southern Sudan, where none had operated for many years due to the war, had long been considered. On 20 May 2002, Dr. Lual Deng, the SPLM’s Banking and Finance Committee chairman, made the bold statement that the SPLM would establish the Nile Commercial Bank by June 2002 and introduce a new currency by the end of 2002.[2] Plans were evidently in place to establish the bank in Yambio, in the Western Equatoria province, by August 2002.

While widely criticized inside and outside Sudan for attempting such an ambitious plan, the SPLM continued with their strategy. In September 2002 it was reported[3] the Economic Production Commission of the SPLM/A would launch the New Sudan pound in October 2002. (‘New Sudan’ is the name given by the SPLM/A to southern Sudan.) This report was followed in the ensuing months by several other reports, stating the proposed introduction of the new currency.

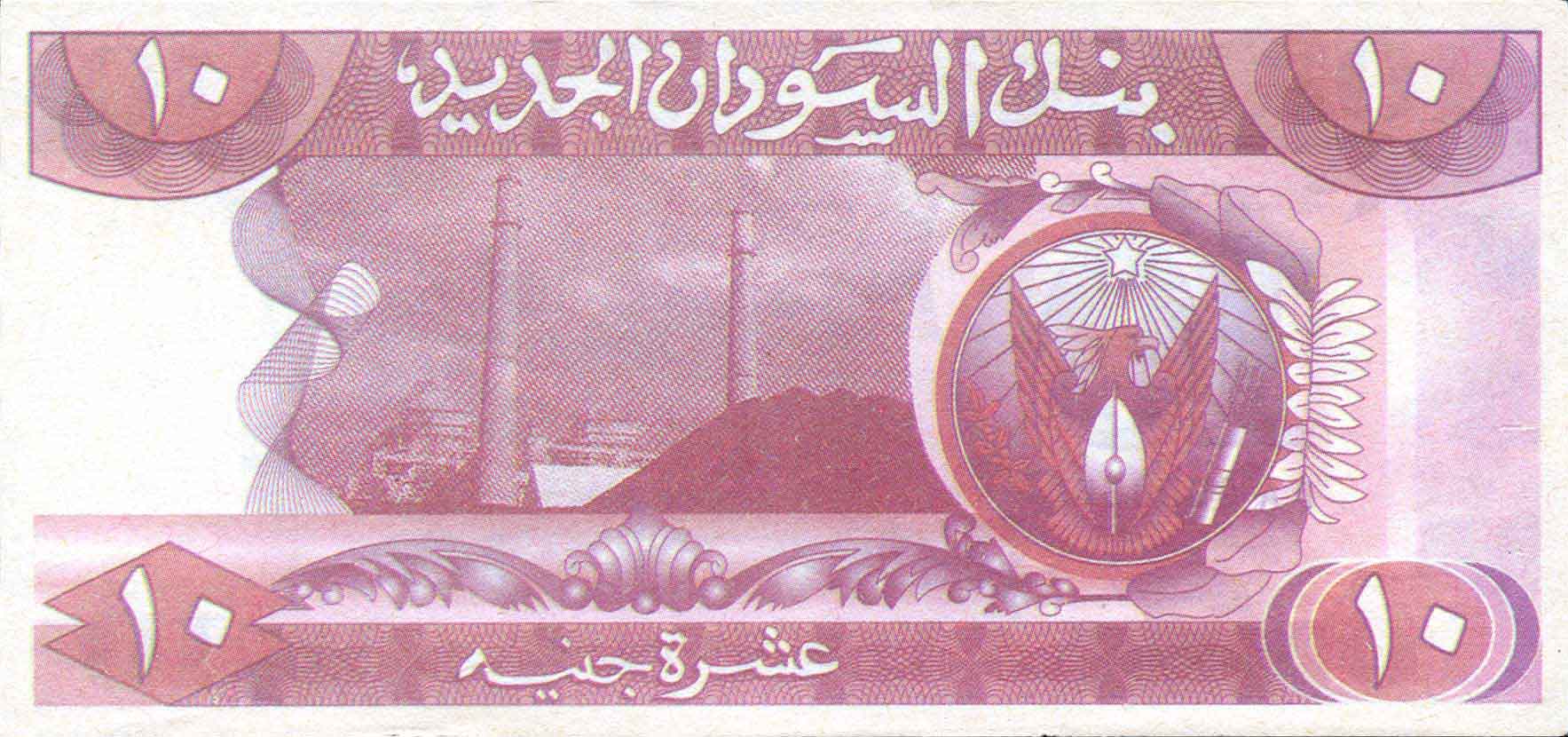

In November 2002 a report surfaced indicating the new currency was to be issued in December 2002. A poster displaying specimen notes was said to have been distributed throughout southern Sudan, advising of the imminent release of notes denominated in 1, 5, 10, 25, 50, 100 and 200 pounds. The report stated the notes had been prepared by two Asian businessmen in Kampala, Uganda, under contract by the SPLM/A’s Economic Production Commission.[4]

This announcement brought fresh attacks from the government of Sudan. At this time the government and the rebels had been conducting peace talks in Machakos, Kenya, and the government accused the rebels of placing the talks in jeopardy through their planned actions. The rebels responded, saying they believed parallel systems could work in Sudan and John Garang believed the move was in line with the Machakos Protocol, agreed in July 2002, which recognised three distinct areas of the south, the north and the central regions of Sudan and allowed for parallel systems in the north and south.[5] The rebels also re-iterated they required a non-Islamic banking system and a currency which did not impose Islamic ideals on them. By mid-December 2002 the SPLM/A had printed some 60 tonnes of the new notes and it was rumoured they were about to introduce them.[6]

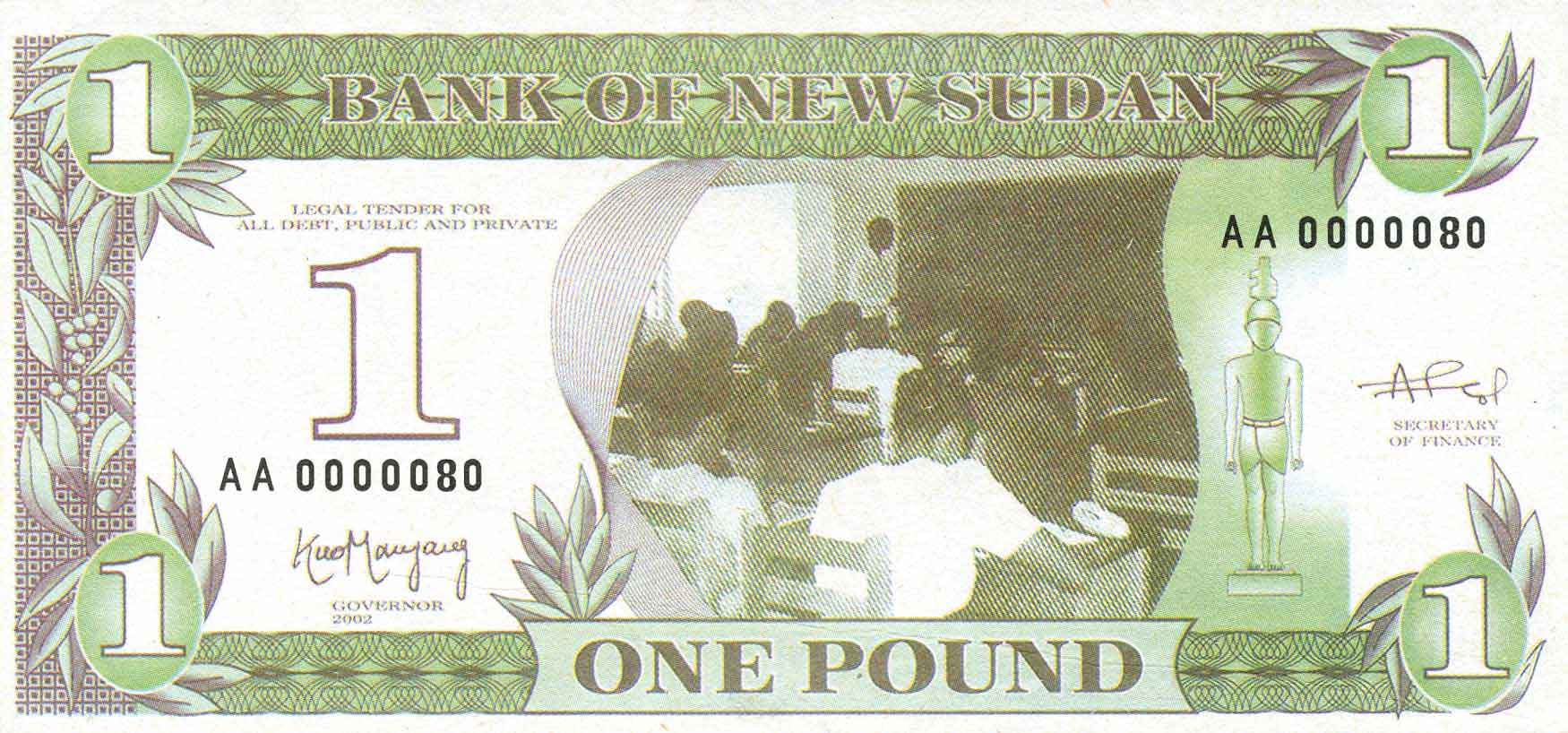

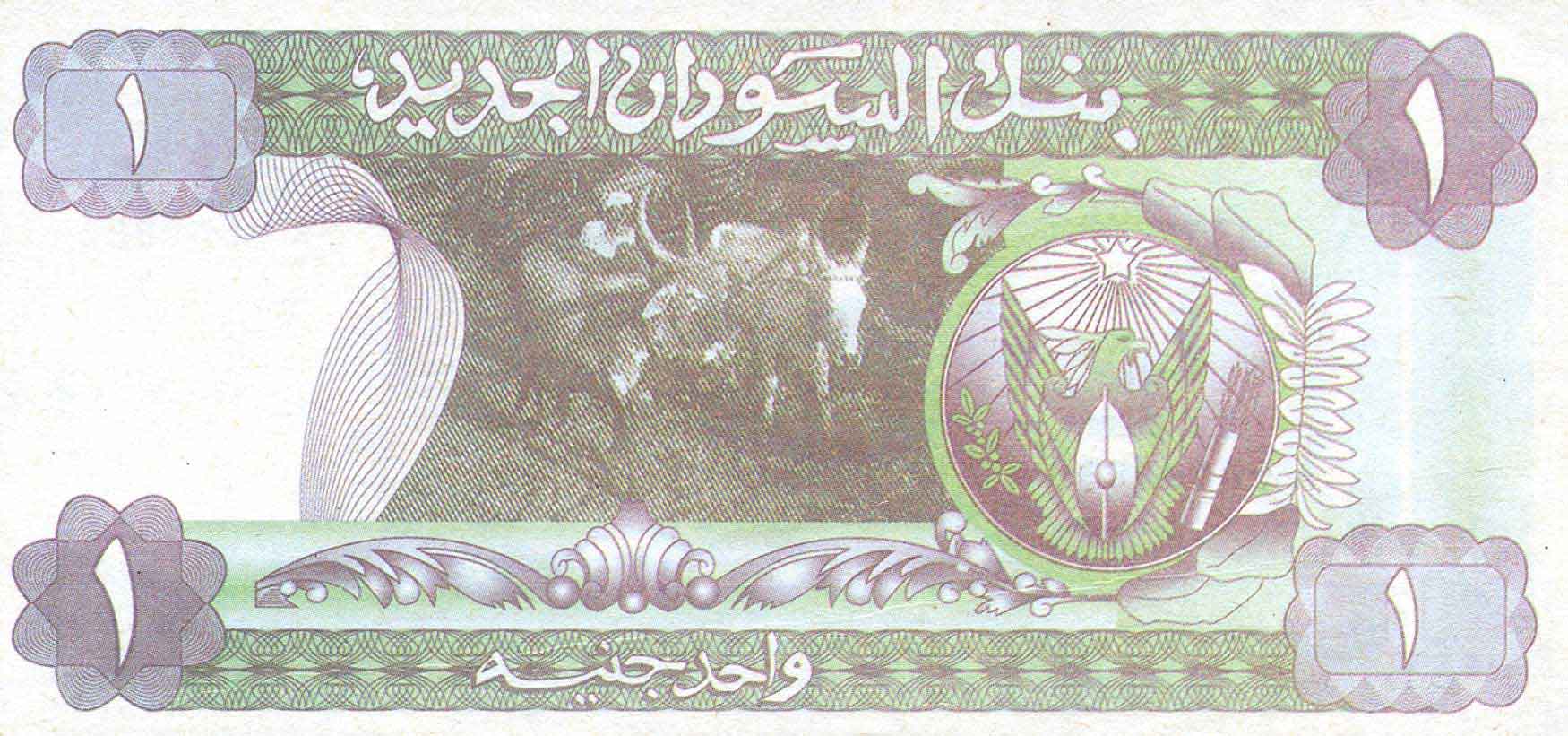

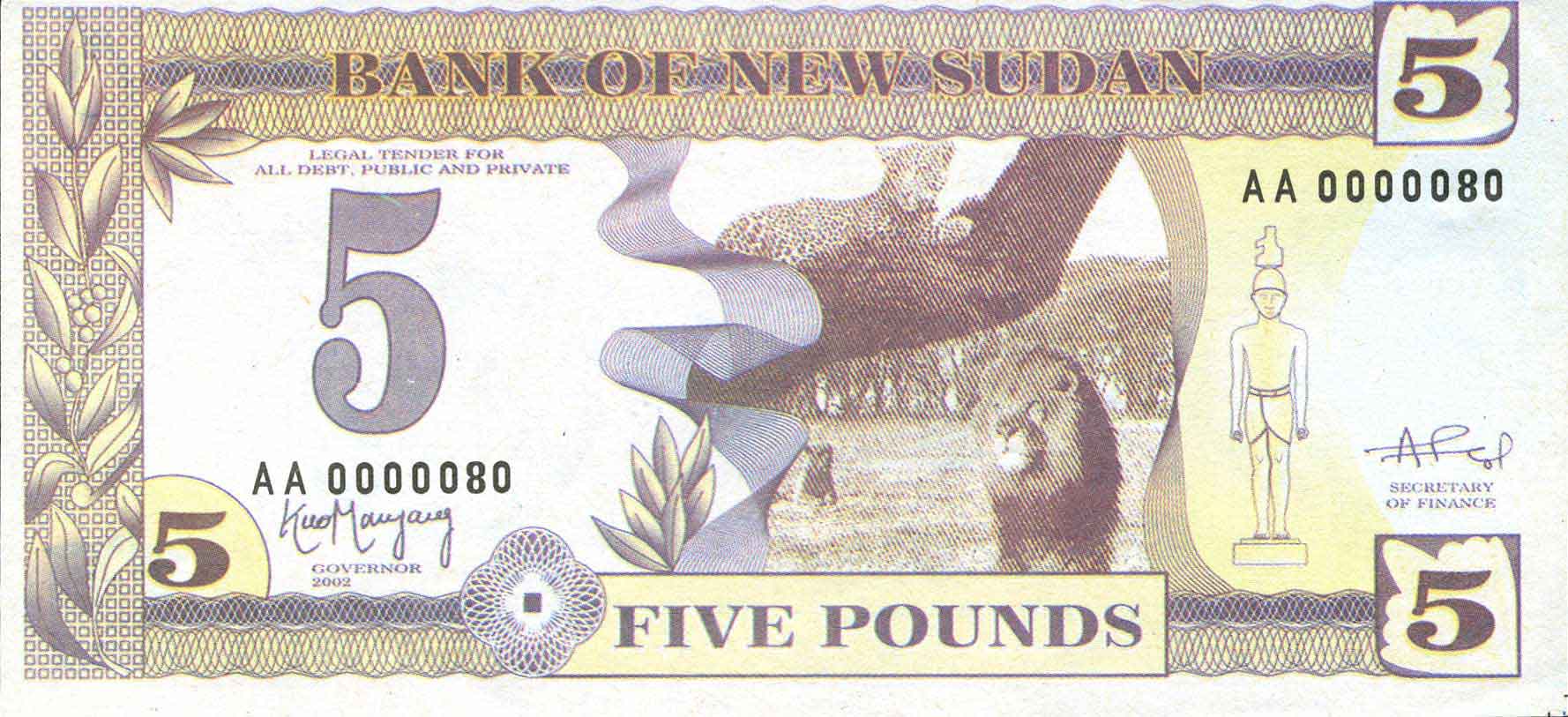

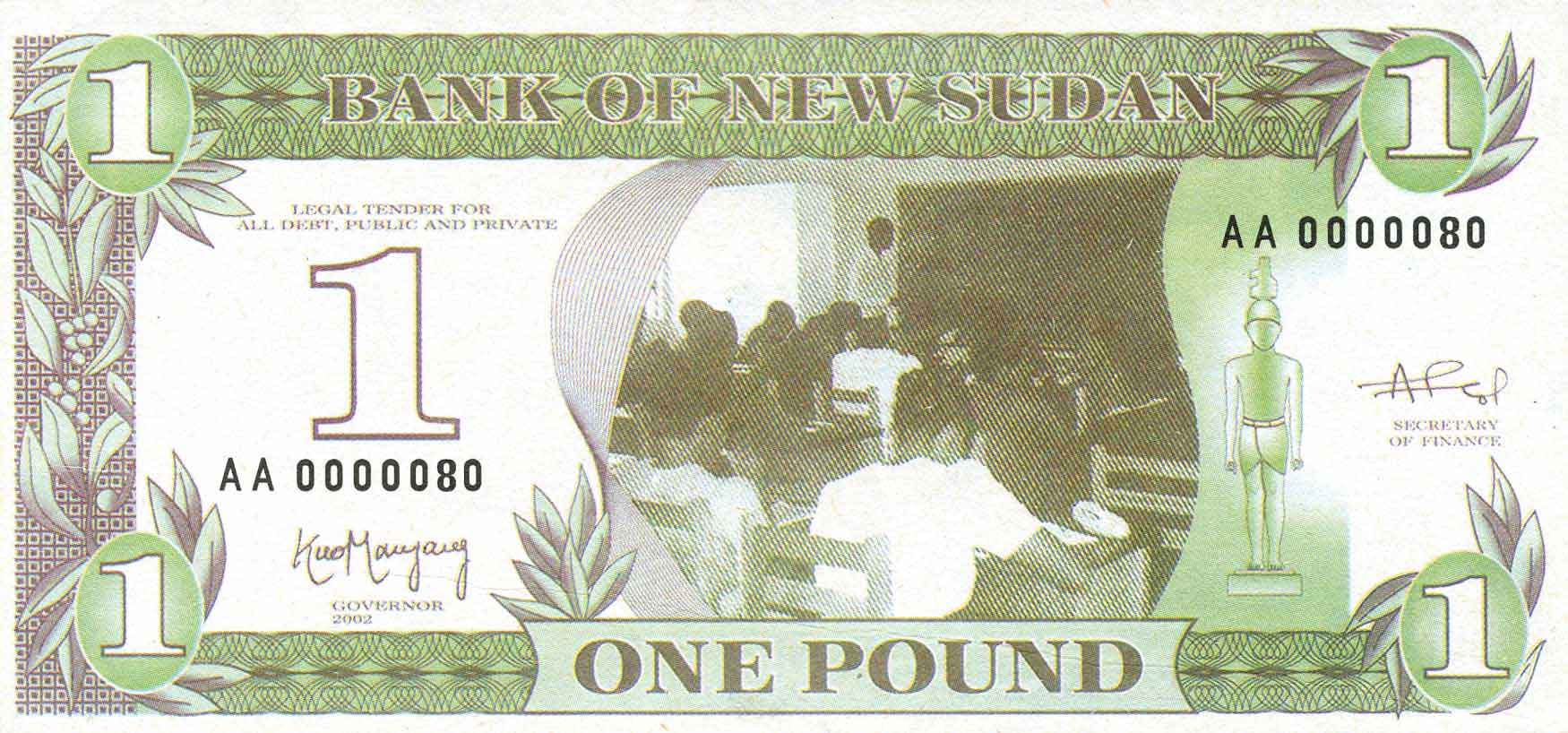

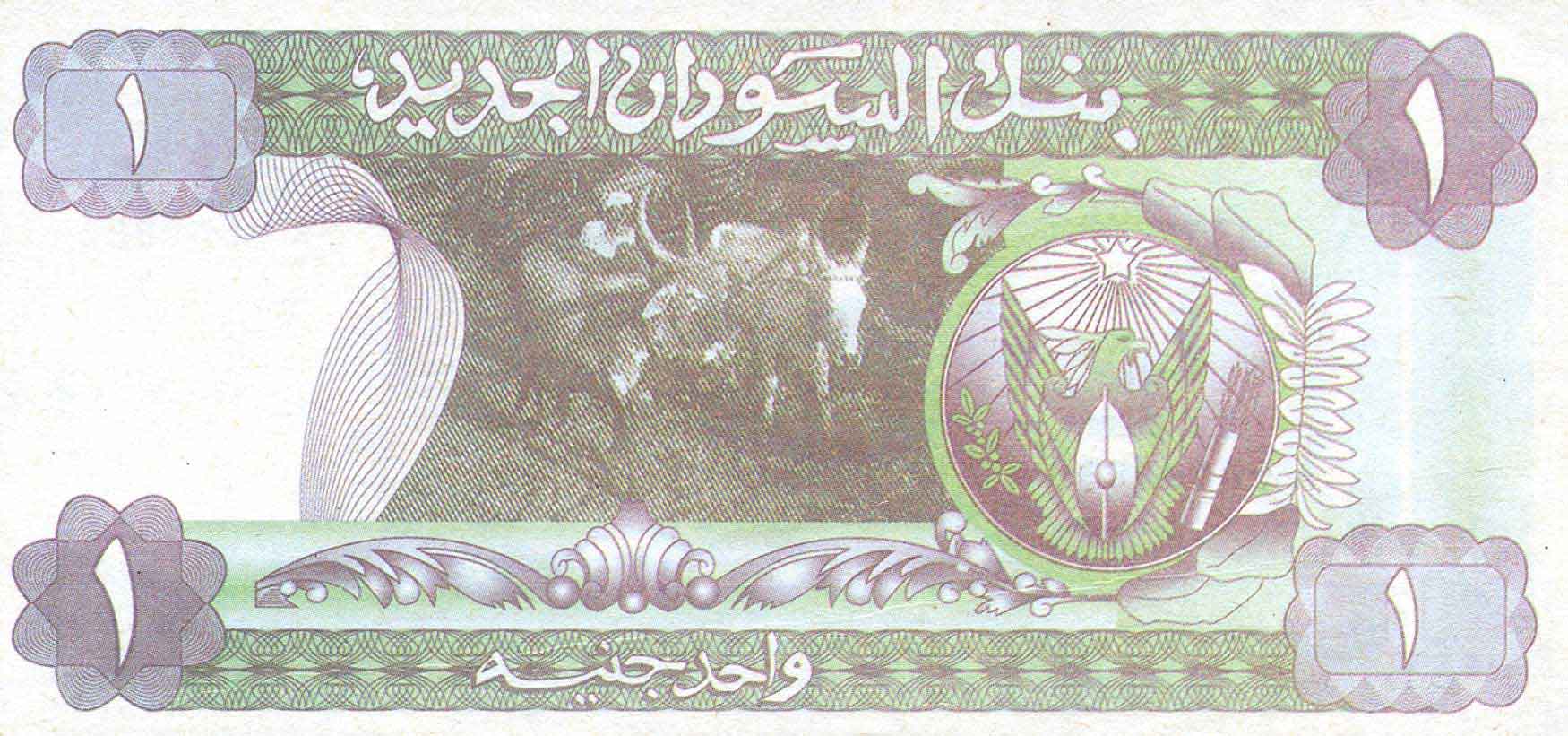

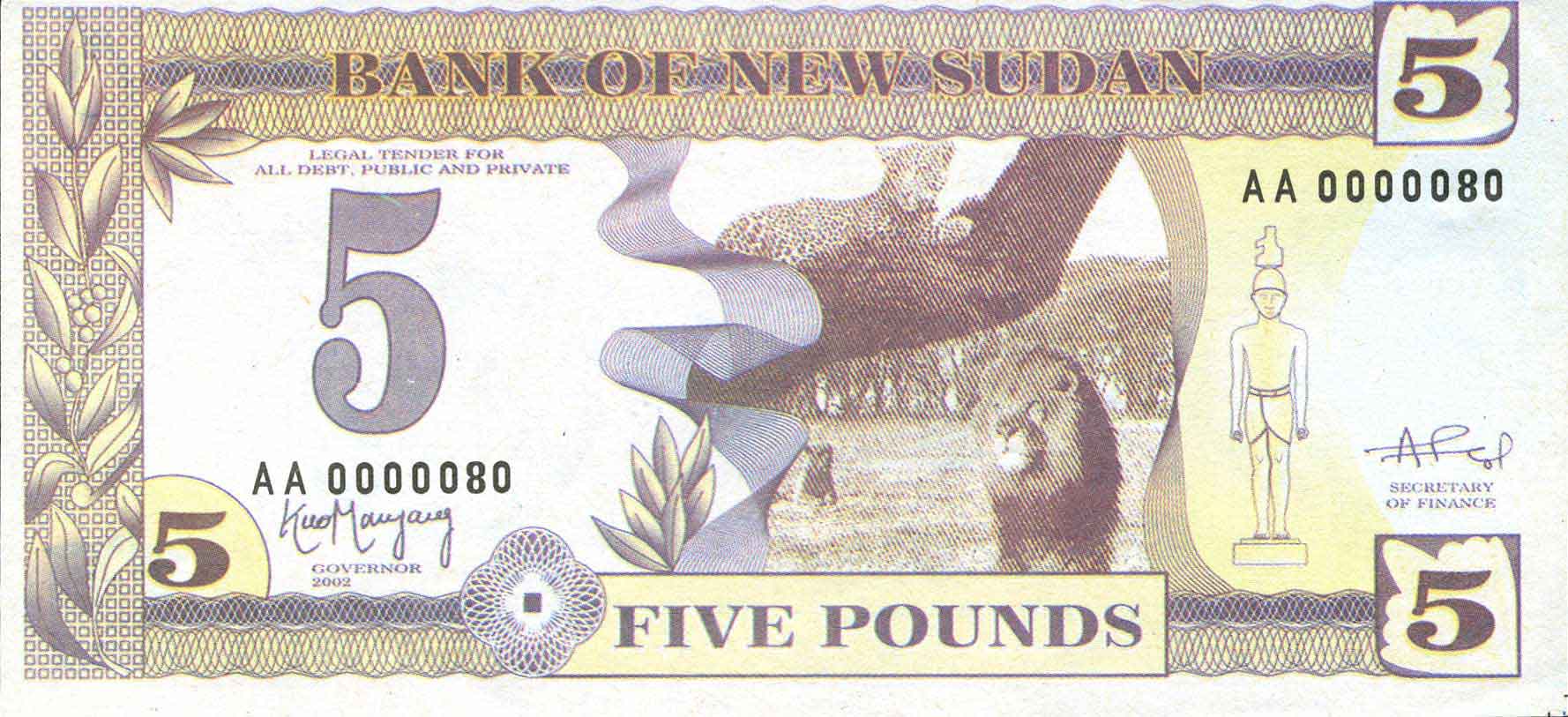

The notes of the Bank of New Sudan are quite rare, with very few examples known among collectors and the details of the designs of the higher denominations are largely unknown. The few surviving examples of the lower denomination notes allow some insight into their design.

The notes have several common characteristics. English text across the top of the notes on the front boldly states ‘Bank of New Sudan’ and the denomination is in bold text at the bottom of each note. At the upper left is the statement ‘Legal Tender for all debts public and private.’ The notes are signed by Kuol Manyang[7] as Governor and Arthur Akuein Chol[8] as Secretary of Finance. Both men were leading figures of the SPLM/A when the banknotes were manufactured and both men continued to be leading figures in the politics of Sudan for many years. Below the signature of the Governor is the date 2002.

Several devices are common to the fronts of the notes. An outline of a statue wearing a kilt and an ornate headdress is at the right; evidently based on an ancient Nubian figure. In a panel at the left is the branch of a plant, which is probably an olive branch, and leaves of the olive tree appear in the upper left and the lower centre.

On the back of the notes, the common elements are: the Arabic text of the name of the bank and the denomination of the note; the coat of arms of New Sudan; and decorative panels of leaves. The coat of arms is based on the coat of arms of Sudan, with a secretary bird and a shield. However, this rendition of the coat of arms sees the bird with an olive branch in one claw and a quiver of arrows clenched in the other – showing the ability to act in war and peace. Above the head of the bird is a star, which also appears on the flag of New Sudan.

Each denomination has images of Sudanese people, countryside or infrastructure on the front and back:

Although evidence is scant, it appears the notes of New Sudan were not introduced as early as intended. Reports on their circulation at this time cannot be found, however in a speech to celebrate the 22nd anniversary of the founding of the SPLA in 2005 (see below), shortly after the notes were known to be placed in circulation, John Garang stated the notes were ‘circulating before’ the recent introduction – suggesting the notes might have been placed into circulation for a short period in 2002 or 2003.

Whatever the facts about the introduction of the notes around 2002, the bank proposed by the SPLM/A, the Nile Commercial Bank, was founded on 8 March 2003.[9] Shortly after, on 29 June 2003, John Garang signed The Central Bank of New Sudan Act[10], which repealed The Central Bank of the New Sudan (Provisional Order) 2000. Of interest in the act to establish the Central Bank of New Sudan is Clause 26, which states: “The Bank shall determine the design of the bank notes issued by it, but no bank notes shall bear in its design a portrait of a living person or any political symbol or word.”[11] Although enacted by the SPLM, there is no evidence any such institution was actually established.

The world press remained silent on the currency of New Sudan until 2005 when, in May of that year, problems with a ‘new currency’ in southern Sudan were being reported, identifying the notes causing problems as those previously prepared by the SPLM/A for circulation in 2002.

According to press reports, in April 2005 the SPLM declared all old and foreign currencies – including US dollars – circulating in areas controlled by them had to be exchanged for new Sudanese pounds. The exchange was controlled by the Nile Commercial Bank although there was little official oversight of the exchange. The old Sudanese notes presented for exchange were burned so they could not be used again.

The new notes of the Bank of New Sudan were used, but evidently not well liked by the southern Sudanese. In some areas the new notes were trading at a discount in the local markets. Cheaply produced, many of the notes had no serial numbers, many had the same serial number and the local people regarded them as fakes or not real. Printed on ordinary paper, the notes were easily torn, the ink ran when they became wet, colours varied and the printing was often not clear. Officials of the Nile Commercial Bank admitted the notes were of poor quality, but said there was no reason to be concerned about counterfeiting, as anyone found guilty of counterfeiting the notes would be shot.[12]

A mystery surrounding the introduction of the New Sudan pound is the timing. In January 2005 the SPLM signed the Comprehensive Peace Agreement with the Khartoum government and under that accord the Sudan government agreed to introduce a new currency to replace the dinar. Having gained the objective of a new currency in January, why would the SPLM/A introduce the New Sudan pound in May? An unflattering view of the introduction was reported in October 2005 as:

“The currency is a particular problem in the south, where people reject the Sudanese dinar, and use US dollars or Kenyan and Ugandan shillings instead. Not helping the fact is that one of Southern Sudan’s less savoury individuals, Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA) commander Kuol Manyang, recently made a rather self-serving and very pedestrian, but ultimately futile, attempt at enriching himself when he launched the ‘New Sudanese pound’. When businesspeople from Kenya asked to buy some of the new currency, they found not only was there no exchange rate, but also that the new pound was photocopied – and bore Manyang’s signature.”[13]

This view might be a little unfair on Kuol Manyang, who was now a significant player in the new government and who was no longer in the position he held in 2002 when he signed the notes. It is likely the notes were released by the SPLM/A hierarchy but the part played by Kuol Manyang in their release is unclear. Of interest is a speech made by John Garang at Rumbek on 16 May 2005, on the occasion of the 22nd anniversary of the founding SPLA. In the speech, made just 12 weeks before he died in an aircraft crash on 30 July 2005, he stated:

“The currency just issued in Rumbek is not a new currency; it is old notes of the Sudan Pound, which was circulating before, that has been reissued as happens in any economy since notes get worn out; that is why the exchange value is the same. I understand the quality of the paper of the currency is poor and that there are other technical problems. These will be solved and the notes improved to standard quality, and the New Sudan pound at the same market value as the old notes will continue to circulate until when both the New Sudan pound and the dinar are replaced by a new joint currency agreed by the parties [to the Comprehensive Peace Agreement].”[14]

How widely the New Sudan pound circulated is uncertain; one report states the SPLM/A’s notes were circulating only in Juba.[15] In another interesting move, the Nile Commercial Bank, previously the bank responsible for introducing the New Sudan pound was, by March 2006, introducing the dinar into Western Equatoria state for the first time since the war between the north and south broke out.[16] It appears, in view of a currency shortage and unstable currency situation, the SPLM/A supported the use of the dinar, which had previously been rejected. The introduction of the dinar in the south at this time caused problems; having spent years being educated not to accept the notes, many traders rejected them.

Following the introduction of new 50-, 10- and 1-pound notes to replace the dinar (at 1 pound to 100 dinars) in January 2007, the Bank of Southern Sudan, was responsible for the conversion of the new currency with the old currencies in the south. In April 2007 the Director of the Bank of Southern Sudan, Kornelio Koriom Mayik, noted several problems in introducing the currencies. First, he estimated there were 36 billion Ugandan shillings, 9.7 billion Kenyan shillings and 12 billion Ethiopian birr circulating in southern Sudan – all of which had to be exchanged. Second, he noted there were problems in Rumbek with two versions of the pound circulating, the original issues of the Bank of Sudan and the ‘new notes of the former pound’, i.e. the banknotes issued by the Bank of New Sudan. So, by April 2007 the New Sudan pounds of the SPLM/A were still circulating in some areas of southern Sudan, over a year after the notes were introduced.

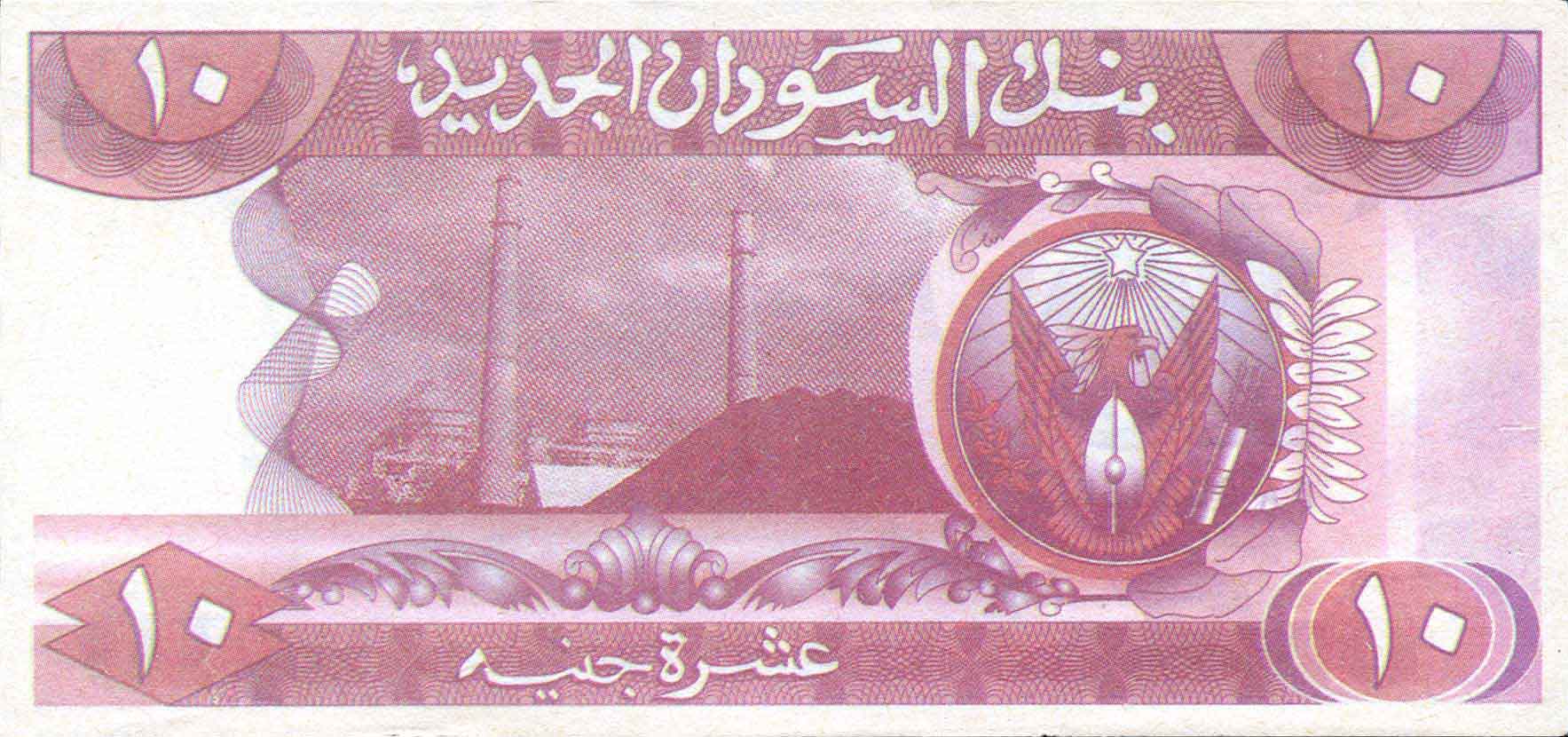

Although the banknotes of the Bank of New Sudan were collected during the program of converting dinars to the new pound – from January to July 2007 – the SPLM-produced notes were not honoured in redemption, as they were never regarded as legal tender by the Sudanese government. These notes, along with all notes presented for exchange, were taken to Khartoum and destroyed by the Central Bank of Sudan. What is peculiar about the New Sudan pounds is they did not find their way on to the collector market. Only a very few are held in collector’s hands, despite an expectation the notes would flood the market at some stage. Images of the 50- and 100-pound notes have not been seen, although it is probably some exist with a few lucky collectors.

|

|

| The front and back of the lowest denomination note, 1-pound, prepared for the Bank of New Sudan. |

|

|

| The Bank of New Sudan’s 5-pound note. This is the only denomination (of those seen) where the word for ‘pound’ appears in Arabic in the lower cartouches holding the value of the note at the bottom left and right on the back of the notes. |

|

|

| The 10-pound note prepared for the Bank of New Sudan. |

|

| The 200-pound notes, from a NPR program by Jason Beaubien. |

This article was completed in January 2011

© Peter Symes